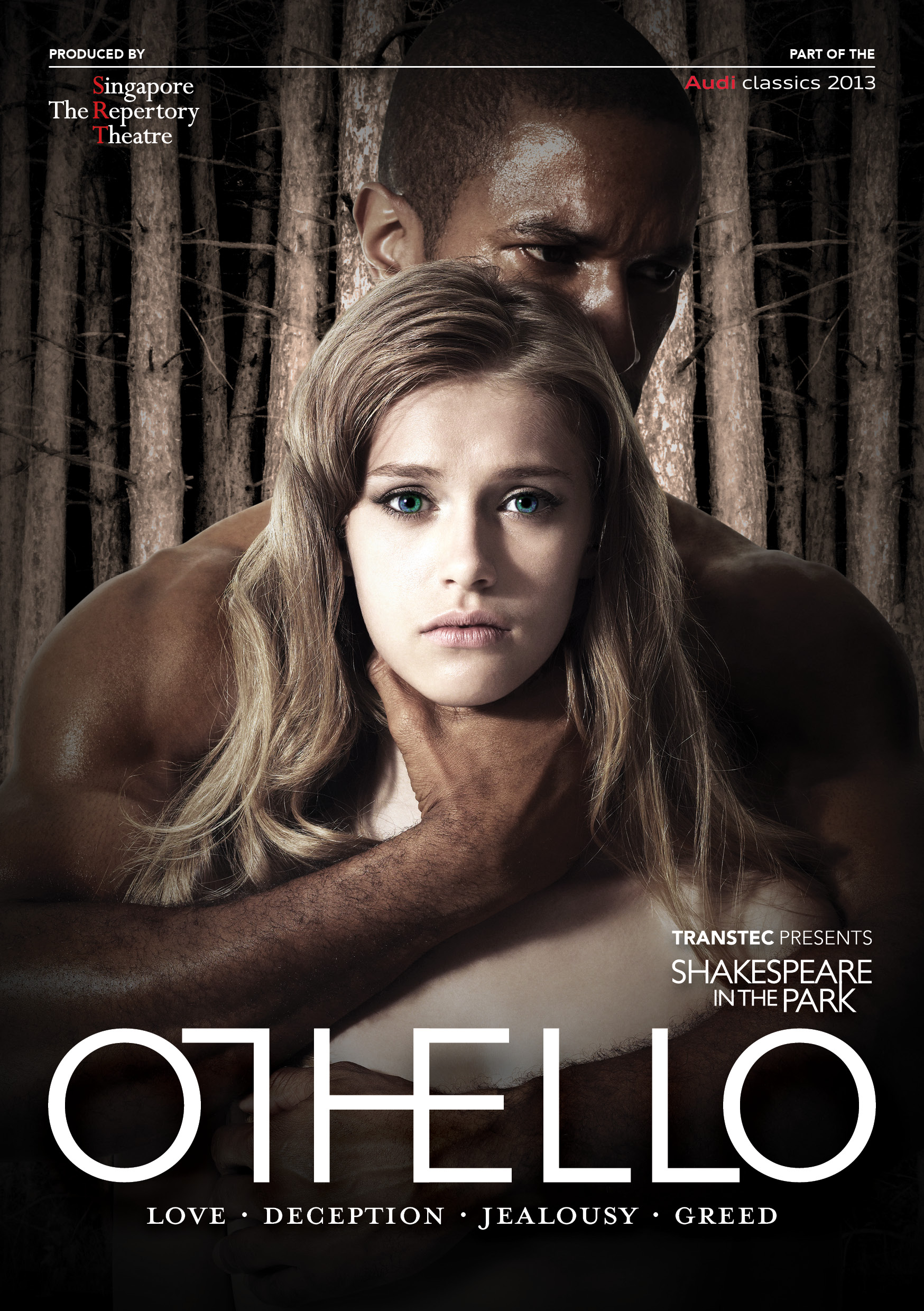

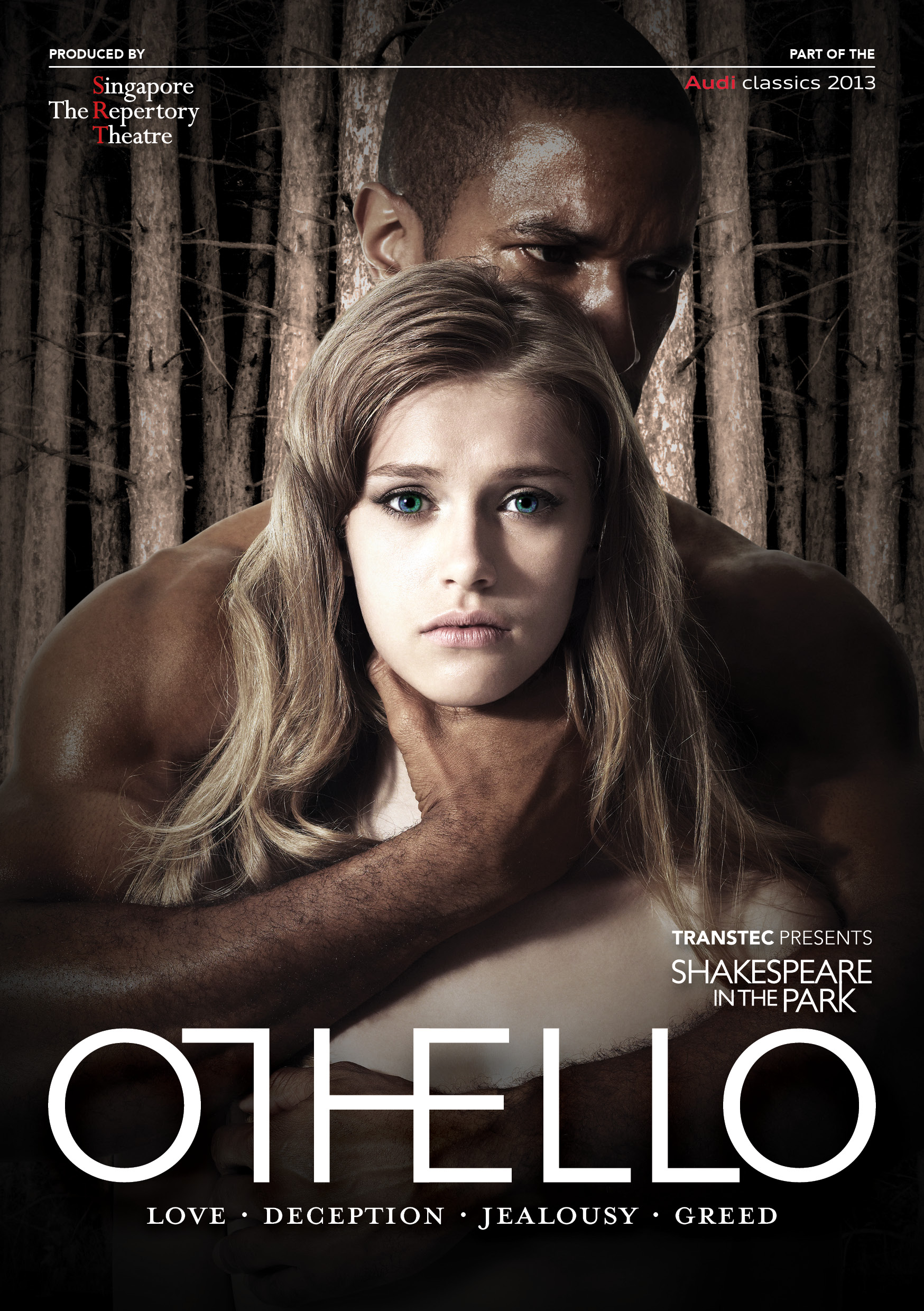

The full title of the play is “The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice,” written by William Shakespeare in 1603. 31, 2023) – North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University’s Theatre Arts Program tackles one of Shakespeare’s most intimate family tragedies beginning Feb. Natural Resources and Environmental Design NewsĮAST GREENSBORO, N.C.Leadership Studies and Adult Education News.Journalism & Mass Communication English.Industrial and Systems Engineering News.Electrical and Computer Engineering News.Computational Science and Engineering News.Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering News.Chemical, Biological, and Bio Engineering News.Agricultural and Natural Resources News.Agribusiness, Applied Economics and Agriscience Education News.

Administration and Instructional Services News. In cinemas across the UK from 23 February and around the world on 27 April via NT Live. This is an Othello which feels unlike any other, its central figure a villain not a hero – a cleaning up of the play, indeed.Īt the National’s Lyttelton theatre, London, until 21 January. It remains highly watchable and well-paced with good supporting performances from Rory Fleck Byrne as the earnest Cassio and Jack Bardoe as Roderigo. The chorus seem to represent inner demons they bring creepiness, but also mystifying scenes such as one in which they emerge in masks, holding police shields. The thriller tropes are effective but overdone, with thunder, rain, jagged sounds, drumbeats, fire embers on a back screen, sudden spotlights and swirls of darkness. The production does not seem entirely joined up in its vision, veering from what resembles Greek tragedy (there is a miming chorus) to modern melodrama. The opposite of Mark Rylance’s cerebral and apparently unassuming Iago, Hilton has an over-egged comic villainy and appears like a cross between a Marvel-style Joker figure and a pantomime baddie who might have mistakenly wandered off the set of the theatre’s adjacent show, Hex. Paul Hilton’s Iago, meanwhile, is the hammiest character on stage. We watch him unravel but feel disdain when he claims to have loved his wife “too well” after murdering her. Terera, for his part, appears a contemporary figure while bearing the legacy of slavery on his body (a patchwork of laceration scars on his back). She appears as Othello’s equal, despite her paucity of lines, and while she and Giles Terera’s Othello do not have a passionate chemistry, there is tenderness and mutual respect between them, until he turns on her. Rosy McEwen is quietly radical in her role as Desdemona too, never simpering or scared. Murky performance history … Peter Eastland (Ensemble) in Othello at the National Theatre. It is an almost obvious interpretation, once we have seen and heard it, yet it makes the play feel utterly new. The women are not reduced to victims here while the men, including Othello, are controlling, toxic abusers.

Administration and Instructional Services News. In cinemas across the UK from 23 February and around the world on 27 April via NT Live. This is an Othello which feels unlike any other, its central figure a villain not a hero – a cleaning up of the play, indeed.Īt the National’s Lyttelton theatre, London, until 21 January. It remains highly watchable and well-paced with good supporting performances from Rory Fleck Byrne as the earnest Cassio and Jack Bardoe as Roderigo. The chorus seem to represent inner demons they bring creepiness, but also mystifying scenes such as one in which they emerge in masks, holding police shields. The thriller tropes are effective but overdone, with thunder, rain, jagged sounds, drumbeats, fire embers on a back screen, sudden spotlights and swirls of darkness. The production does not seem entirely joined up in its vision, veering from what resembles Greek tragedy (there is a miming chorus) to modern melodrama. The opposite of Mark Rylance’s cerebral and apparently unassuming Iago, Hilton has an over-egged comic villainy and appears like a cross between a Marvel-style Joker figure and a pantomime baddie who might have mistakenly wandered off the set of the theatre’s adjacent show, Hex. Paul Hilton’s Iago, meanwhile, is the hammiest character on stage. We watch him unravel but feel disdain when he claims to have loved his wife “too well” after murdering her. Terera, for his part, appears a contemporary figure while bearing the legacy of slavery on his body (a patchwork of laceration scars on his back). She appears as Othello’s equal, despite her paucity of lines, and while she and Giles Terera’s Othello do not have a passionate chemistry, there is tenderness and mutual respect between them, until he turns on her. Rosy McEwen is quietly radical in her role as Desdemona too, never simpering or scared. Murky performance history … Peter Eastland (Ensemble) in Othello at the National Theatre. It is an almost obvious interpretation, once we have seen and heard it, yet it makes the play feel utterly new. The women are not reduced to victims here while the men, including Othello, are controlling, toxic abusers.

This other play is about the tragedy of domestic violence. A new vision does come though, breathtakingly so, in a radical half-hour at the end when it feels as if Dyer is revealing another play beneath the story we know about jealousy and mistrust in which Othello is a flawed hero who commands our sympathies. It sets up a conceptual overhaul – a coming clean, of sorts.īut we are wrongfooted in the sense that, for much of its three hours, this Othello plays out as a traditional thriller that occasionally veers into melodrama. There are posters of old productions projected on to Chloe Lamford’s spare, contemporary set and a cleaner scrubs the floor. Clint Dyer’s new production speaks to the play’s murky performance history in its opening optics, perhaps even to the ghost of Olivier’s Othello himself. I n 1964, the National Theatre Company staged Othello with Laurence Olivier playing the military commander in blackface.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)